It's a haunting reminder, the obelisk in Draketown, of things of the past that have never been widely known, or even solved.

Two local "history detectives" have returned with their new book, "Draketown Tragedy," a Prohibition-era that recounts murder, conspiracies, moonshiners, the Ku Klux Klan and the Roaring Twenties.

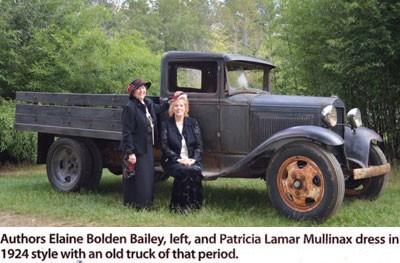

Elaine Bailey, author of "Explosion in Villa Rica," teams up with Patricia Lamar Mullinax, author of "In the Line of Fire," to delve into the history of the monument in Draketown that is dedicated to Alice "Wildie" Adams Stewart.

Draketown is in Haralson County, near Highways 113 and 120, straddling both Carroll and Paulding counties.

The story began some residents say, in 1907 when Georgia voted that whiskey was to be illegal, years before Prohibition.

Temperance movements were common in the North where Massachusetts passed such a law in 1838, more or less a citation, banning the sale of alcohol drinks in less than 15-gallon quantities. But that law was repealed two years later. The first state prohibition law was enacted by Maine in 1846 and several other states followed suit before the Civil War.

The ratification of the 18th Amendment to the U.S.Constitution in the early 20th century became known as the Volstead Act but the legislation was difficult to enforce, and west Georgia, especially Haralson County, was ripe for the illegal production, transportation and sale of liquor, known as bootlegging.

Trisha Mullinax was a 10-year-old in 1957 when she first encountered the 15-foot, white marble obelisk in Draketown. The image was instilled in her mind for 30 years when Arreda Bingham Denton happened to stroll into Hair Villa Salon in Villa Rica where Mullinax was employed.

Denton had so many stories about the 1920s in Haralson County, specifically Draketown, and the Stewart story, that she and her new hairstylist became close friends and the tale of sadness that Denton carried all those years was finally transferred to another person.

The Villa Rica Salon eventually became a small library for many people who had heard of the stories, and more people showed up every week to listen to Denton's history lessons.

After Denton died in 1994, Mullinax began jotting down her remembrances of the tales spun by Denton about Draketown in the 1920s.

Twenty years later Mullinax joined forces with history author Elaine Bolden Bailey and the two spent two additional years poring through libraries, archives, courthouses, interviews with relatives near and far, and anyone who would agree to explain what actually occurred in 1924 in Draketown.

"Many relatives of those individuals still residing in Georgia were hesitant to provide any oral histories and archival information ,"Bailey said. "Since the events leading up to the murder of Rev. Robert Stewart's wife, Alice Stewart, and the aftermath, some of the heirs were very reluctant to discuss anything that may point to a relative being a bootlegger, indicted for certain crimes, including homicide, and those who were witnesses and testified otherwise."

The most promising data, other than Denton's validations, came about when one of Rev. Stewart's daughters, Lorene, years later contacted Julie Colombini, Alice Stewart's great-granddaughter . who was living in Japan. Lorene Stewart Butler, as a birthday present to Colombini, chronicled the history of her mother's fate and the monument erected by the KKK in Draketown.

Why was the Klan involved, and who killed Alice Stewart? Why were the felons, murderers and moonshiners not convicted of any crimes, except for three people who, in federal court, received five years only?

- Geoff Parker, The Times Georgian

Where is the moonshiner's automobile with the large hole in the side, shot there by Reverend Robert Stewart 91 years ago in Draketown? Why did the moonshiners attempt to abduct the pastor? Why did they shoot the pastor's wife, Alice, twice - once in the back when she lay face down?

These questions are answered in the new book, Draketown Tragedy, by local co-authors Elaine Bolden Bailey and Patricia Lamar Mullinax.

"Arreda Bingham told me what happened in Draketown when she came into the beauty shop where I worked in 1989. For almost 30 years I've wanted to write this story," explained Trisha Mullinax.

Trisha shared this story of what happened in 1924 to Alice Stewart in Draketown with her friend, Elaine Bailey, who had written a novel Tracks; and, the non-fiction The Explosion in Villa Rica. Elaine was drawn in and for the next year and half these two local ladies researched Draketown history and interviewed historians and old timers in Haralson and adjacent counties.

"For the first six months of research, we came up with more questions than answers," Bailey said. "Where were the court records? Why were the newspapers from 1924 through 1926 missing from the county libraries?"

When interviewing the older folk, they were told, "Oh, we don't talk about that. That was a long time ago." That's what their parents had told them when they questioned why the white marble, 15 foot obelisk stood in the center of Draketown.

For 91 years, people have wondered about the monument and why it was there. Despite an inscription on the side, questions remain.

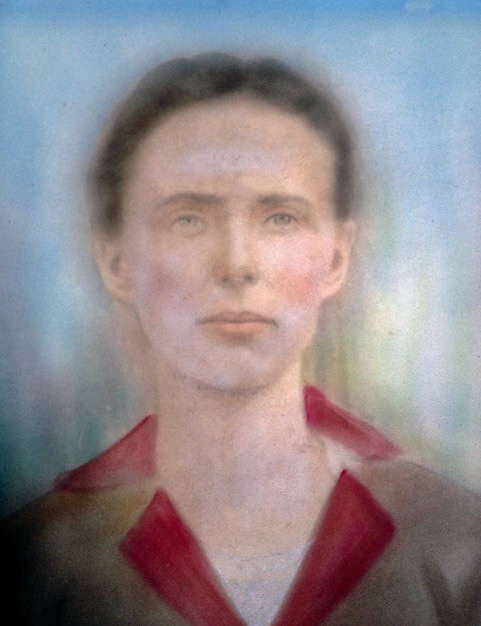

"Our breakthrough came when we found Alice Stewart's granddaughters who gave us the oral history and shared amazing photographs," related Bailey.

"Our greatest dilemma in writing this book was .telling the story of the moonshiners, explained Bailey. "Ten men were arrested. Some were released immediately; five went to trial. No one was convicted for the murder of Alice Stewart. No one paid for her death.

"Even though the newspapers printed the names of the accused," Bailey continued, "we changed the names since descendants still live in the surrounding counties. Changing some of the names means the book is 'fiction based on fact.'"

Meet the authors, who will be reading excerpts from the book at the book signing for Draketown Tragedy, on March 12, 2016 from 1:00 - 3:00 p.m. at the New Georgia Public Library, 94 Ridge Road, Dallas, Georgia 30157.

- Elaine Bailey, The Dallas New Era, Feburary, 24th 2016

Murder in Draketown

In retrospect, the Rev. Robert Stewart had been asking for trouble.

As a circuit preacher in the Roaring Twenties of Prohibition, he had preached against the evils of alcohol from various pulpits, especially from that of the District Line United Methodist Church in Draketown. But he did more than that. With a pistol strapped to his hip, the preacher and members of his congregation would range into the woods and bust up the stills of moonshiners.

That earned him a nickname, "The Raiding Parson." But it also earned him an evil name among bootleggers who ran their liquor to Atlanta and to farm folks all around. They vowed to teach him a lesson, and on the night of Nov. 13, 1924, they struck.

Yet, it wasn't the preacher who paid the price; it was his wife. When evil men came by their parsonage to drag Robert Stewart away in the night, it was Alice Stewart who stepped out to challenge them with the preacher's own gun. The criminals shot her down and left her bleeding in the street.

The story of that fateful showdown in Draketown made the front pages of newspapers across the nation, but nearly a century later it has largely been forgotten. Two local authors, however, don't want that to happen.

Elaine Bailey, who has authored several books, including one on the 1957 Villa Rica natural gas explosion, recently teamed up with another resident, Patricia Mullinax, to tell the story of the "Draketown Tragedy." Both are hopeful that moviemakers will now take up their mission and bring the story of Alice Stewart to an even wider audience.

Draketown, located at the intersecting borders of Haralson, Carroll and Polk counties, was a farming community of some size in the days before the Great Depression. But it had already faced its own economic disaster because of the fall in cotton prices and the devastation of the boll weevil, which took away the region’s cash crop.

In their book, Bailey and Mullinax discuss the hardships of farmers who scrounged for scraps to feed their families. In such times, it was easy for desperate men to be tempted by the easy cash of making and selling illicit alcohol. National prohibition, a Constitutional ban on selling booze, had been in effect since 1920, but Georgia had been dry since 1907. Since then, there had always been a market in Atlanta for the moonshine cooked along the creeks and in the woods of west Georgia.

Stewart had made it his mission in life to not only preach against the evils of alcohol, but to put his words into action. The bootleggers, who expected trouble from deputies and state revenue agents, resented Stewart meddling in their affairs. On at least two occasions they warned him to stop — once, in fact, they dropped off a fake casket on his front porch that had his initials carved into the lid.

On the night of Nov. 13, 1924, three carloads of men pulled up to the parsonage in the middle of the night. Posing as still-smashers, they woke Stewart and tried to convince him to go along with them on a liquor raid. But Stewart was suspicious and turned to go back to his house. That’s when the men in the cars revealed their true intentions.

One of the men grabbed him from behind and they started to pull him into one of the vehicles. “Damn you,” another abductor shouted, “You have made your last raid!”

The ensuing struggle raised a ruckus that seemingly was heard by everyone in the community, but only one person came to the reverend’s aid: his wife, Alice.

Still clad in her nightgown, the preacher’s 35-year-old wife picked up the pistol Stewart carried on his raids and ran toward the scuffle, begging the men to let her husband go. When they didn’t, she fired two shots in their direction.

Someone in one of the cars fired a shot that ripped into Mrs. Stewart’s arm, causing her to spin around and fall to the ground still gripping the weapon. Then came another shot that struck the helpless woman in her upper back, shattering her spine and instantly paralyzing her.

The bootleggers now panicked and struggled to get away in their vehicles, tossing the woman off the street and out of their way. Stewart broke away from his would-be abductors and ran to his wife’s side, where he picked up the weapon and fired wildly at the cars as they roared away. Those in the vehicles fired two more shots as they disappeared into the dark.

There were two doctors in town and they were at Alice’s side within moments. Both doctors concluded that they had to get her to an Atlanta hospital as fast as possible. As they headed out on rough roads, a posse gathered to go after the bootleggers.

Alice lingered for two days at the hospital, paralyzed by her injury, before she died on Nov. 15. In the meantime, the story of the courageous woman who stood up to moonshiners got picked up on newswires and went to every newspaper in the country.

Eventually, 10 men would be arrested, some of whom had been identified by Stewart. But none of them were ever convicted of the crime.

In June 1925, more than 5,000 people gathered in Draketown for the unveiling of a 15-foot tall monument that marked the spot where Alice, now considered a martyr to Prohibition, had been shot down.

Mullinax said she had often seen that monument, but she — like many other local residents — did not know the story behind it. But then a customer at the beauty salon where she worked began to tell her stories about the old days and hard times of Draketown, including the story of Alice Stewart.

Eventually, she got Bailey interested in writing the book, which they completed in 2015.

Through mutual friends, they have contacted someone who may be able to help them tell the story through a movie. They believe the story is so dramatic and such an important part of local history that it deserves such a treatment, and they will have meetings with their contact later this month.

The monument, unveiled so long ago, is still there on Eaves Drive in Draketown, its meaning largely lost to modern-day folks. It once had a ceramic portrait of Alice, but that was before vandals took it. Yet the inscription remains:

“Alice Wildie Adams, wife of the Rev. Robert Stewart, Born May 10, 1888, assassinated Nov. 13, 1924, by rum runners at this place and died at Wesley Memorial Hospital, Nov. 15, 1924. She was a kind and affectionate wife, a fond mother and a friend to all.”

Then the monument includes two verses from Proverbs, intended to teach a lesson about the wages of sin wrought from the evils of drink:

“At the last it biteth like a serpent and stingeth like an adder.”

- Ken Denney, The Times-Georgian, Janurary, 11th 2020